Dr. Thomas Gold And Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents: Part 1

Hydrocarbon Chains from the Earth's Mantle Emit from Deep Sea Hydrothermal Vents.

This substack article is an extract from my book The Truth About Energy, Global Warming, and Climate Change: Exposing Climate Lies in an Age of Disinformation.

In chapter 2 of his book The Deep, Hot Biosphere: The Myths of Fossil Fuels, Thomas Gold discusses the 1977 deep-sea-diving submarine Alvin’s exploration of deep-sea vents along the East Pacific Rise, northeast of the Galapagos Islands. The Alvin found an “ocean bottom teeming with life” that lived at ranges “far below the deepest possibility for photosynthetic life.” A searchlight revealed life was teaming around cracks in the ocean floor that appeared volcanically active in an otherwise barren sea. Here is how Gold described the sea life the Alvin found:

The patch was covered with dense communities of sea animals—some exceptionally large for their kind. Anchored to the rocks, these creatures thrived in the rich borderland where hot fluids from the earth met the marine cold. New to science were species of lemon-yellow mussels and white-shelled clams that approached a third of a meter in length. Most striking of all were the tube worms, which lurk inside vertical white stalks of their own making, bright red gills protruding from the top. Like the tube worms of shallow waters, these denizens of the deep live clustered together in communities, with tubes oriented outward resembling bristles on a brush. But unlike their more familiar kin, the tube worms of the deep are giants, reaching lengths in excess of two meters.[1]

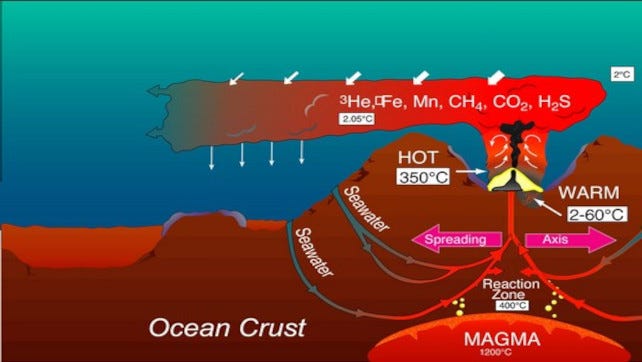

Further investigations soon found similar hydrothermally active vents in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. In each case, streams of milky fluids and black “smoke” emerged from the seafloor vents. Gold postulated that the hydrocarbon gases venting through volcanically active cracks at the bottom of the sea provided the nutrients these sea bottom microbes and bacteria needed to live at depths where there was no light. “These streams of hydrothermal fluids, heated and enriched in gases and minerals, are now known to be the sources of chemical energy at the base of the vent community’s food chain,” he wrote.[2]

In 2000, the Alvin found a remarkable ecosystem in the mid-Atlantic Ridge at depths of four to five miles below the ocean’s surface. Termed the “Lost City,” this hydrothermal field was living off deep-Earth hydrocarbon, venting out from calcium carbonate chimneys that reached up almost one hundred yards from the ocean floor. Scientists from the School of Oceanography at the University of Washington in Seattle, joined by scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, were part of an international team to investigate the Lost City hydrothermal field (LCHF). The international team included Swiss scientists from the Department of Earth Sciences at ETH-Zentrum in Zürich. In March 2005, the oceanographic scientific team published their findings in Science.[3] They reported that the serpentinite-hosted Lost City hydrothermal field was “a remarkable submarine ecosystem in which geological, chemical, and biological processes are intimately interlinked.”

Here is how they summarized their findings:

TheReactions between the seawater and upper mantle peridotite produce methane- and hydrogen-rich fluids, with temperatures ranging from <40° to 90°C at pH 9 to 11, and carbonate chimneys 30 to 60 meters tall. A low diversity of microorganisms related to methane-cycling Archaea thrive in the warm porous interiors of the edifices. Macrofaunal communities show a degree of species diversity at least as high as that of black smoker vent site along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, but they lack the high biomasses of chemosynthetic organisms that are typical of volcanically driven systems.[4]

These results appeared to support Gold’s hypothesis of sea-bottom life deriving nourishment not from photosynthesis. These sea-bottom creatures, including microorganisms, lived off the abiotic hydrocarbons venting from deep within Earth onto the seafloor through the tall, white carbonate chimney structures of the Lost City.

[1] Thomas Gold, The Deep Hot Biosphere, p. 11.

[2] Ibid., p. 12.

[3] Deborah S. Kelley, Jeffrey A. Karson, et al., “A Serpentinite-Hosted Ecosystem: The Lost City Hydrothermal Field,” Science, Volume 307, Issue 5714 (March 4, 2005), https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.1102556.

[4] Ibid., “Abstract.”